Strong scientific research underpins biotech boom in San Diego

[THE INVESTOR] SAN DIEGO -- What if we could simply take a protein-control pill to get in sync with our circadian rhythm, curing the dreaded symptoms of jet lag once and for all? How about reversing the natural aging process -- literally becoming younger -- via genetic modification processes?

These are just some scenarios that could one day become a reality through ongoing research at the Salk Institute of Biological Studies in San Diego, California, one of the key players underpinning the city’s booming biotechnology sector.

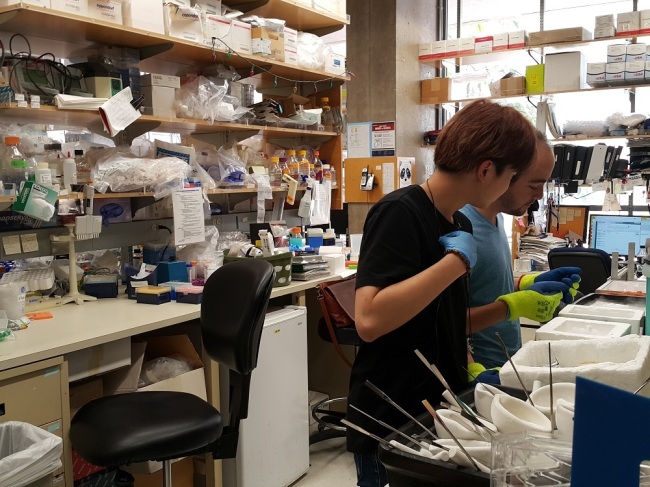

Scientists work inside the Salk Institute’s Regulatory Biology Laboratory, led by Satchin Panda

Founded in 1960 by Jonas Salk, the developer of the world’s first polio vaccine, the Salk Institute is one of the city’s most influential life sciences research bodies, alongside the Scripps Research Institute and the University of California, San Diego.

Located on a hilltop facing the Pacific Ocean, Salk has produced six Nobel Laureates since its foundation. It houses 55 independent laboratories dedicated to major fields like aging and regenerative medicine, cancer biology, immune system biology, metabolism and neuroscience.

Some of the institute’s latest scientific breakthroughs include the discovery of a protein called Rev-ErbA, which acts like a switch that turns on or off the genes that regulate our circadian rhythm -- the 24-hour cycle that governs the physiological processes of living organisms.

If controlled artificially, this protein could lead to a cure for various conditions and illnesses linked to a disruption in the circadian rhythm including jet lag and sleeping disorders.

Another lab at Salk has managed to successfully rejuvenate the organs of laboratory mice and increase their lifespan, considered the preliminary steps toward reversing the key markers of aging among living organisms, including humans.

Drawing some $118 million in annual funding, 44 percent of which is government-based, Salk focuses on “basic biological research” that forms the backbone of new therapeutics development and biotech innovation.

So far, 38 biotech companies were spun off of or inspired by Salk Institute discoveries, while 569 US and foreign patents covering Salk technology have been issued, according to the institute.

By relying mostly on government grants such as those from the state-run National Institute of Health, Salk has remained independent from corporate interests in its pursuits. The institute also receives grants from private foundations and individuals.

“New scientific discoveries require lots of experimentation and exploration,” said Amandine Chaix, a scientist at Salk’s Regulatory Biology Laboratory led by Satchin Panda, during a tour of the institute last week.

“That’s why we don’t really cooperate with drug companies (particularly in the early stages of research) because they often require a final product right away. You need the flexibility to explore scientifically, and later you can hopefully arrive at a new drug or treatment,” she said.

Salk’s focus on flexibility is also embodied by its culture of active collaboration, in part encouraged by the unique architecture of the institute’s world-famous buildings.

Designed by American architect Louis Kahn, Salk’s lab spaces are all connected with no physical walls between them with aims to encourage an open and collaborative working culture.

“All of our labs are open. If I have a question, I simply walk over directly and ask my colleagues what I want to know right away. It’s very easy to engage in discussion,” Chaix said.

Powered by continued scientific research and talent coming from places like Salk and backed by tax-friendly policies, San Diego has developed a flourishing biotechnology cluster driven by an advanced genomics industry.

Much of the region’s biotech sector growth was originally initiated by scientists from institutions like UCSD that launched entrepreneurship programs including “Connect” in 1985, which encouraged academics to start their own companies, including those in biotechnology.

San Diego’s biotech sector has since grown exponentially, with an exclusive strength in genomics. Genomics research strives to determine complete human DNA sequences and map out genes to help understand and treat diseases.

As of 2016, the city’s genomics sector created an annual economic impact of $5.6 billion, affecting 35,000 jobs, according to a report by the San Diego Regional Economic Development Corporation, a nonprofit organization that channels investment into the region’s core economic sectors, including biotechnology.

The city prides itself on its “end-to-end” genomics industry. It handles every aspect of the genomics value chain from sampling and sequencing led by companies like Illumina and Thermo Fisher Scientific, to analysis and interpretation by Human Longevity and clinical applications by firms like Celgene and Arcturus Therapeutics.

Behind the city’s rapid biotech growth is a stable workforce trained in the life sciences. According to the EDC, San Diego confers nearly 2,000 genomics-related degrees per year, benefiting both genomics companies and top academic institutions in the region.

According to the San Diego Regional EDC’s chief biotech and life sciences consultant Bill Bold, the city’s biotech business growth was partly influenced by the generous tax incentives and funding offered to firms looking to settle in the area. However, what mattered more were the fundamentals -- strong science and a steady pool of qualified life sciences experts.

“In our experience, tax incentives matter, but they matter far less than the foundation of the research institutes and the workforce,” said the SD Regional EDC’s chief biotech and life sciences consultant Bill Bold.

According to Bold, the most important aspect of a successful biotech cluster is a research university structure that engages in quality research as well as graduates students who will be making the new discoveries and novel products in the life sciences.

And this is a lesson that South Korea should also keep in mind as it works to belatedly forge its own biotech clusters in cities like Songdo, said the EDC’s biotech consultant.

“If you’re trying to establish a cluster, ensure that there are adequate research institutions in the country, either existing, new or expanded, that have some sort of physical or business connection to the cluster region,” Bold advised.

“In other words, if Korean universities are not keeping pace with American, Chinese universities, the cluster is not going to be as successful, because it’s that public-private partnership that makes the foundation of every successful cluster.”

By Sohn Ji-young/The Korea Herald (jys@heraldcorp.com)

EDITOR'S PICKS

- Seoul shares rattled by Israeli attack on Iran; Kospi dips to nearly 11-week low

- S-Oil donates W560m to support firefighters

- LG CNS teams up with Yonsei University to nurture AI specialists

- Polestar 4 to make Korean debut in June

- S. Korea pledges W23tr venture capital fund for green investment at G20 meeting

- Sungsimdang outperforms bakery giants to log sales over W100b

- France rejects opening Paris flight routes to T'way Air, deals blow to Korean Air merger

- SK hynix chief underscores chip cooperation between Korea, US